On this page I share a curated selection of product case studies covering some of the main product areas I’ve worked on. This list is not comprehensive, but the stories themselves are highly representative of my work. Though I can’t provide specific details in some cases due to confidentiality, the lessons remain highly illustrative.

My current team, Digital Life Science Solutions, manages and develops products to support life science research. Specifically, these products empower life scientists by saving them valuable time, effort, and materials when designing and validating experimental procedures. The oldest platform product in the portfolio is Springer Nature Experiments - the largest discovery platform specializing in life science protocols and methods. New product is ‘Methods Muse’, an AI-powered research assistant/co-scientist system that accelerates experimental design, troubleshooting, and validation.

digital life Science SOlutions

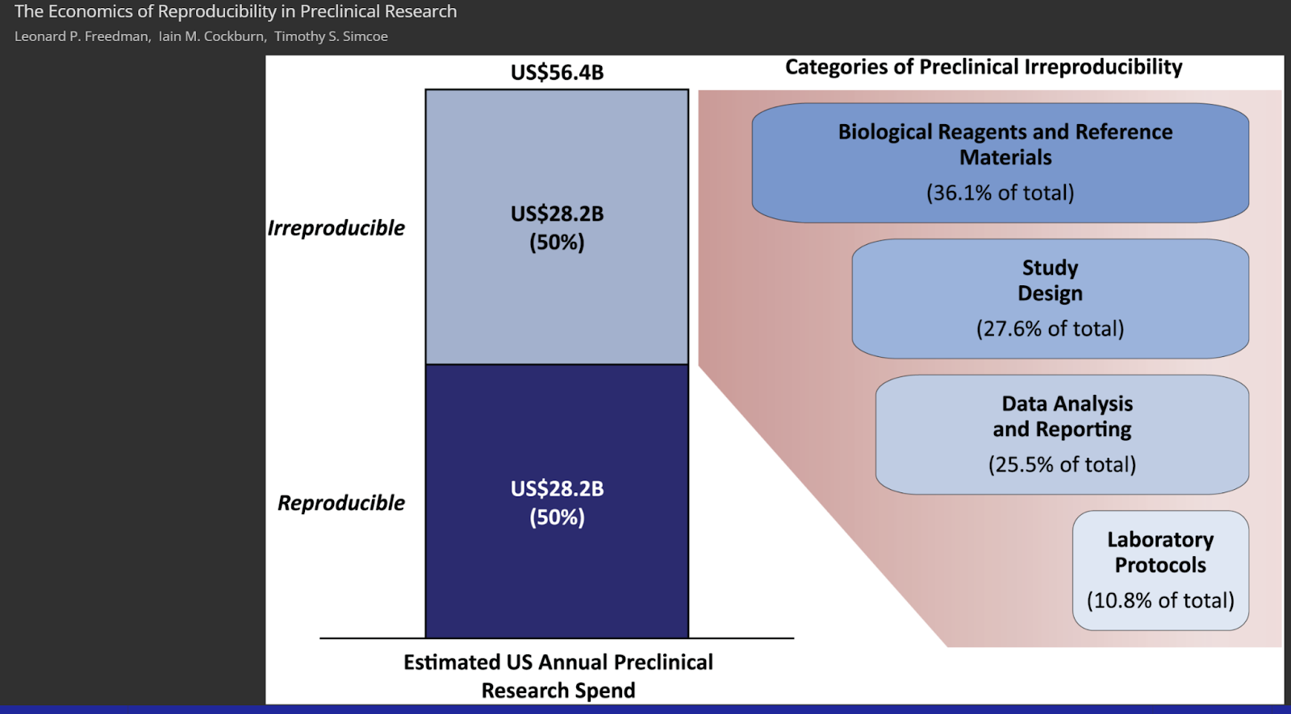

Zero to Launch: An AI-based Life Science Research Assistant

Problem: Lab protocols are the unsung heroes the research lab. Protocols contain detailed, step-by-step instructions on how to achieve a specific results (e.g., purify a protein, grow cells, analyze genomics datasets, etc.). These procedures are the foundation of lab research as they ensure reproducibility. Despite this importance, problems with lab protocols and reproducibility abound, hampering research progress. A staggering amount of time, money, materials, and effort are wasted, on reproducibility problems - one study estimated up to $28 billion per year is wasted in preclinical R&D alone (see below). Reproducibility is thus a clear opportunity space where good solutions are desperately needed.

Solution: The scale and complexity of life science reproducibility is enormous. Where does one even start? Leading a product team that builds digital products for life scientists, I approached the problem as a scientist would: from first-principles. We developed a solid understanding of the main problems researchers face, based on extensive quantitative and qualitative research and product analytics. The uncovered insights gave us a sense for what attributes a good solution should have. For example, any solution should comprehensively cover as many subject areas as possible. The solution should also go beyond being a search tool since the most severe user pain points centered around designing and optimizing procedures plus troubleshooting failed experiments. The solution should thus be an extension of what a researcher does when designing and validating experimental results. But how might we build such a solution?

Artificial intelligence.

I’m going to be blunt - I’m an AI realist. I think the absurd levels of AI overhype are really frustrating because the noise just obscures the genuinely transformative opportunities. It’s true that no one needs a generative AI-powered toothbrush. And yet the AI boom, with its ongoing deluge of large language models, vector database solutions, agents, and many other tools, really do offer a solid foundations for a new solution to the abovementioned

Building on our well-established product discovery process, my team ran through multiple rounds of prototype testing, both lo-fi and hi-fi, to access fundamental desirability, feasibility, and commercial viability. Using AI as part of the process was, in fact, a game changer. User interview analyses were done in hours instead of days. Workable, ‘vibe coded’ prototypes let us rapidly our hypotheses. And yet, we never answered all questions had during testing . We therefore resorted to a well-established (and personal favorite) testing method: open beta testing of new platform Methods Muse.

Impact: There were many noteworthy aspects to launching this new AI-powered system. To start, Methods Muse is part of the ‘first wave’ of new Springer Nature products built around generative AI to reach the market. Next, Methods Muse launched as a public beta version, or a field test as I like to call it. My team reached the limit of where smaller scale research and ideation could take us: the only way forward collecting real-world usage data to address key questions around things like usability and performance. Though uncommon in the digital life science space, open beta testing is a fantastic method for gathering usage data at-scale and for keeping a close contact with users. Open beta testing also falls under my general preference for Open Innovation, as detailed at length here.

The results were very encouraging - during the test run we achieved returning user percentages of ~33% and consistently achieved USAT scores ≥ 80%. The insights we gained on things like user prompting, AI evaluation, technical integration were invaluable to understand the value and potential of the Methods Muse solution. For example, we expanded our product development to now cover agentic workflows (e.g., building out MCP servers). We also realized that integrating the Methods Muse capabilities on various platforms would be a tremendous value add. The first (of hopefully many) examples of this integration is with the protocols.io platform.

Despite the fast changing nature of AI-systems, researcher behaviors, and the competitive/collaborative spaces, we can be confident in our ability to quickly build (and utilize) AI-based solutions that are delivering real outcomes instead of riding hype cycles.

(Rapidly!) Supporting COVID-19 Detection with Digital Solutions

Problem: In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic upended life on earth. Leading a life science product team meant aligning with company-wide efforts to support the global pandemic response. The Springer Nature Experiments platform had content on coronaviruses, then an obscure topic. However, we needed ways to better source and display this now critical data. Another challenge was organizational: operating with a Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe) meant collaboration between Product, Design, and Engineering didn’t allow for sudden changes to the delivery plan.

Solution: Consulting with my counterparts in UX and Engineering, I suggested something radical: blow up the delivery plan and also let the product managers, designers, and developers work directly together to tackle the problem, completely abandoning the SAFe framework. There was fast, unanimous agreement and the team quickly began working on a solution.

Considering the stage of the pandemic (Feb/March 2020), we focused on surfacing and displaying protocols related to coronavirus detection. We quickly developed a data tagging method (first manual, later automated) to surface content on coronavirus detection. Identifying the content, however, was only the first step. The next step focused on how to display this data. After some quick experimentation internally and using the data and insights we previously had, we put the solution live.

Impact: Searches for coronavirus and COVID-19 exploded from near non-existent to massive: ‘coronavirus’ and related searches went from <0.3% of searches in 2019 to 67% of searches in April 2020. The COVID-19 detection portal we created drew significant traffic (new and returning visits/ visitors). At its peak (June 2020), the COVID detection portal accounted for 31% of traffic on Springer Nature Experiments. As the pandemic phase shifted to treatment and vaccine development, traffic and usage of the portal gradually declined and stabilized.

For our team, the solution building process was new - and we loved it. Not only did we ship the first version of the COVID detection features in 10 days (from the first, frantic ideation meeting to live), we also realized a completely new way of working. Details on how we developed the solution in such a short time frame are detailed in this Mind the Product article, the first time that a Springer Nature product was ever featured on Mind The Product.

Changing how we worked, which vastly improved our speed and collaboration, eventually led to a transformation in how we worked.

AI Licensing/Data Monetization

Historically, scientific content was consumed in human readable forms like print and PDFs. Now, the shift to digital and machine readable formats along with the explosion in AI applications, has created new business models and product opportunities. Some of my experiences working in the data monetization space are explored below.

Building the Foundations for Growth: Creating a Center of Excellence

Problem: For decades, the scientific publishing has seen waves of transformation (aka “disruptions”). In the 1990s, there was the shift from print to digital platforms. The 2010s were the age of Big Data, and from 2022, the (generative) AI boom kicked off. These waves share one attribute: the need for scientific content to be delivered in new ways for new applications, i.e., a shift from human readable content to machine readable and executable content. This shift also necessitates new business models to reflect the new value propositions.

In this context, Springer Nature’s Data and Analytics Solutions team was organically growing a pipeline of business and product opportunities beyond what our historic products could offer. There was increasing demand for things like customized data sets for text and data mining (TDM) and APIs, with growing customer needs to integrate scientific data directly into R&D workflows. While promising, the heterogeneous nature of the products, markets, use cases, and compliance issues hampered both product and business development. The haphazard, siloed approach of various Product Teams (including mine!) clearly wasn’t scalable.

Solution: Working closely with the department head, I was charged with creating and developing a ‘Data Monetization Center of Excellence.’ My task, in parallel to my full time product leadership position, was to consolidate efforts across Product Teams and establish a scalable foundation. Aligning and working with many stakeholders, I developed an opportunity pipeline tracker, cataloged our data assets, classified use cases by risk and business value, established standardized workflows with support areas like Legal and Finance, and developed new business models proposals. It was a tremendous amount of work, but in a good way!

Impact: Originally, I was leading the Center of Excellence as a ‘side project’ since my own team was actively exploring the space. However, after establishing the foundations mentioned above, it was clear that the Center of Excellence demanded the full attention of a separate, dedicated Product Team. Thus, Springer Nature’s Data Solutions Team was born. Although my time formally leading the data monetization space would end, my own team’s activity in the area continued (see the below).

A New Business Model for a New Digital Lab Use Case

As the following project was never formally publicized, I can neither refer to any public records nor can I disclose specific details about the company.

Problem: While leading the Data Monetization Center of Excellence (see above), a intriguing opportunity presented itself. I was approached by a digital lab startup with a novel value proposition: they were building a voice lab assistant and wanted to partner with my team. Specifically, they wanted to train their machine learning system to improve its voice recognition capabilities (i.e., reduce word error rate). The lab protocols data my team oversees would be a ideal for this use case. After negotiations, we agreed to terms for a pilot project. There was, however, a major blocker. Data licensing for this kind of use case had no precedent. Thus, there were no readily available contracts, workflows, business models, or pricing to use. All of these things would need to be created from scratch.

Solution: Working closely with Legal, Sales, and my team’s product managers and data scientists, I created appropriate structure for the pilot project. My team would create an ML training set based on relevant subject areas. This curated data set would then be used to train a model in a ring-fenced test environment. Improvements to the ML algorithm would then be measured. Depending on the improvement level, different pricing tiers would be in effect - the tiers themselves were agreed upon by all parties. Furthermore, if the success criteria were met, then there would be a clear path to scaling up, from pilot into a full partnership.

The pilot project structure worked well for many reasons. First, since only a small fraction of data was used in the pilot in a ring-fenced environment with very specific reuse terms, the risk associated with data sharing was effectively mitigated. Furthermore, in case of a successful pilot, a scalable commercial agreement could be quickly and easily implemented.

Impact: On a product level, the pilot failed! The improvements to the ML algorithms weren’t as high as expected and the scale-up thresholds were not met. Commercially, however, the pilot was successful. Aside from a successful data licensing deal for the pilot, we also established a noteworthy industry presence.

The impact of the pilot project was wide-ranging. First, this pilot was the first true data licensing deal for a digital lab use case at the company. As such, it was an important proof-of-concept to the wider organization for novel product and commercial opportunities. The project itself was a finalist in the company’s inaugural Innovation Tournament and was well-regarded by executive leadership.

Additionally, this pilot also illustrated a principle that I’ve long been a firm believer in: Open Innovation. When two organizations come together in innovative ways, the result can be a true synergy of value that neither organization alone could deliver. As one of the pioneers of Open Innovation projects at my company, I’ve repeatedly demonstrated the value such partnerships can deliver. Some of these cases are detailed in the ‘Strategic Partnerships’ section.

Springer Materials

Springer Materials is the largest data platform of curated materials science data. Based on the historic Landolt-Börnstein series, the Springer Materials platform has evolved to broadly cover major areas of materials science research and development, such as semiconductors, chemical manufacturing, and energy (perovskite) materials. In this section, I describe two prominent experiences from my first product management role.

Springer Materials Interactive

Problem: SpringerMaterials is well-regarded a compendium of incomparable depth and breadth for materials science data, ranging from mechanical properties of high entropy alloys to semiconductor band gap energies. However, due to outdated workflows, this highly valuable data was ‘trapped’ in the form of PDF documents, drastically hindering machine readability of the data. In an age where (AI-based) computational modeling and simulations are standard approaches in materials science, machine-readable data was desperately needed both to support changing researcher (user) needs and to improve the commercial positioning of the product.

Solution: As the lead product manager, working closely with in-house data scientists and developers, we designed interactive data interfaces that allowed users to both manipulate data on-platform and to the export machine-readable data to their own applications. After analyzing product usage and customer/market data, I determined the interactive datasets should focus on thermophysical properties of organic solution mixtures and then on semiconductor properties.

Impact: The initial rollout was a success. Not only did platform traffic increase by ~10% after solution deployment, but the new functionality moved previously stalled sales negotiations with major prospects. These prospective customers, two major American universities with large materials science research programs, were both converted into now important customers.

A Fabulous Failure

Problem: I had the objective to streamline the experience on the SpringerMaterials homepage. Analyzing platform usage, I determined one feature should be removed: a button leading to a collapsible menu of individual book volumes - books whose original data formed the basis of the platform. My analysis showed that only 3% of homepage visitors clicked the ‘Bookshelf’ button. This observation was corroborated by data that showed searching, rather than browsing, was the user flow to find data. Obviously the ‘Bookshelf’ button could be removed and thus it was.

Unfortunately, removing this button enraged a critical stakeholder: the buyer personas of the product! The backlash to removing the ‘Bookshelf’ button was swift: angry buyers began calling and emailing to voice their fury at removing this button. After being berated for 45 minutes straight by an angry customer, I asked myself: why this backlash over such a little-used feature?

Solution: One of the biggest challenges in B2B product management is the disconnect between the product users and product buyers, who are not the same are rarely interact in many (most?) organizations.

The product buyers for my main customer segment (academic research institutions) needed to justify their purchases to higher ranking budget holders. One of their main arguments was that the SpringerMaterials platform contains huge amounts of data across many materials science areas. This fact was not readily apparent from the clean and simple search bar but it could be more easily visualized with collapsible menus of the bookshelf feature.

The ‘solution’ in this case was then obvious: bring back the ‘Bookshelf’ button but also make it easier to navigate, thus meeting the needs of the economic buyers.

Impact: Reviving the ‘Bookshelf’ feature not only smoothed relations with angry buyers, but also created some good-will with customers. In particular, the responsiveness to listen to buyer needs proved pivotal in retaining key customers at government research labs in North America. To date, this debacle is one of my favorite ‘failure’ stories in my product management career!